Code

import sympy as sp

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

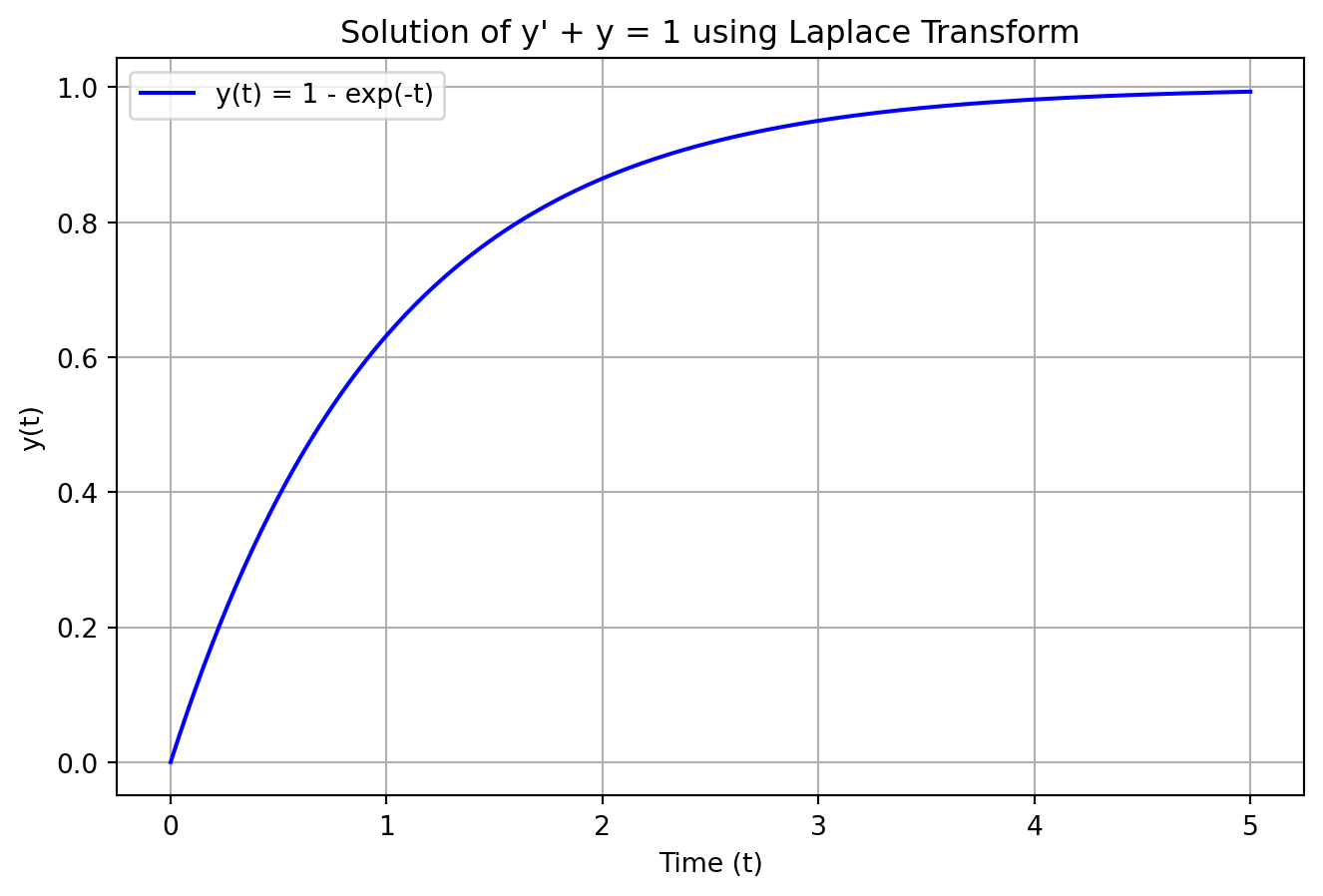

# --- 1. Define Symbols and the ODE ---

t = sp.Symbol('t', positive=True)

s = sp.Symbol('s')

y = sp.Function('y')

# Define the differential equation: y'(t) + y(t) - 1 = 0

ode = y(t).diff(t) + y(t) - 1

# --- 2. Solve directly using SymPy's dsolve with Laplace method ---

# This automates the transform, solve, and inverse transform steps.

# We provide the initial condition y(0)=0 via the 'ics' argument.

solution = sp.dsolve(ode, ics={y(0): 0})

# Display the symbolic solution

print("The symbolic solution is:")

display(solution)

y_t = solution.rhs # Extract the right-hand side for plotting

# --- 3. Visualize the Solution ---

# Convert the symbolic solution into a numerical function for plotting

y_func = sp.lambdify(t, y_t, modules=['numpy'])

# Generate time values for the plot

t_vals = np.linspace(0, 5, 400)

y_vals = y_func(t_vals)

# Plot the result

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 5))

plt.plot(t_vals, y_vals, label=f"y(t) = {y_t}", color='blue')

plt.title("Solution of y' + y = 1 using Laplace Transform")

plt.xlabel("Time (t)")

plt.ylabel("y(t)")

plt.grid(True)

plt.legend()

plt.show()The symbolic solution is:\(\displaystyle y{\left(t \right)} = 1 - e^{- t}\)